It’ll be largely and unsurprisingly overlooked now, smothered beneath the sadness of the passing of his great contemporary, Stirling Moss, but April 2020 would have been the 100th birthday of Duncan Hamilton.

Hamilton passed away in 1994, some 26 years short of his century, but it can hardly be said that he missed out on life. A hugely successful racing driver, he quit at the height of his powers. A life subsequently spent flitting between hobby (sailing) and work (building up his car dealership, which is still in business, run by his son, Adrian) lacked, perhaps, the drama of his earlier life. But then Hamilton, a raconteur of rare talents, would hardly have let us forget...

James Duncan Hamilton was born in Cork city in 1920 and described, in his autobiography, growing up in a city wracked by civil war: “A friend of my father’s was shot at our front door, and more than once bullets splattered into the rooms. We slept on mattresses under the windows to avoid the snipers’ bullets. I was tied to mine, to prevent me looking for the sniper.”

Such tragedies didn’t distract the young Hamilton from mechanical fascinations. He and his father would wait for the parish priest to visit, and then spend the time disassembling and then reassembling the poor man’s bicycle. “How else can the boy learn?” was the justification given to the perplexed pastor.

Hamilton also displayed an early appetite for dangerous adventure, managing to knock himself unconscious by propelling his own pram, himself sat inside it, down a flight of 38 steps. “The memory of the fall receded with the bump on my head; the thrill of the experience remained.”

Following a family move to the UK, Hamilton’s addiction to mechanical devices persisted, fed by trips to the famed Brooklands racing circuit in Surrey. By donning overalls and carrying a bucket of water he used to blag his way into the pits, where he would offer assistance to the bona fide mechanics, ultimately working on the cars of such noted drivers as bandleader Billy Cotton.

Racing would have to take a back seat during the war years, but doubtless Hamilton felt that being at the controls of a Supermarine Seafire and a Westland Lysander, as part of his duties for the Royal Navy’s Fleet Air Arm, was pretty well a case of carrying on the intensity of racing by other means.

Post-war, his racing career began to truly develop, and he was described by no less than works Ferrari driver Froilán as “the world’s fastest wet weather driver.” Gonzales was both countryman and occasionally team-mate to Juan Manuel Fangio, so knew of what he spoke.

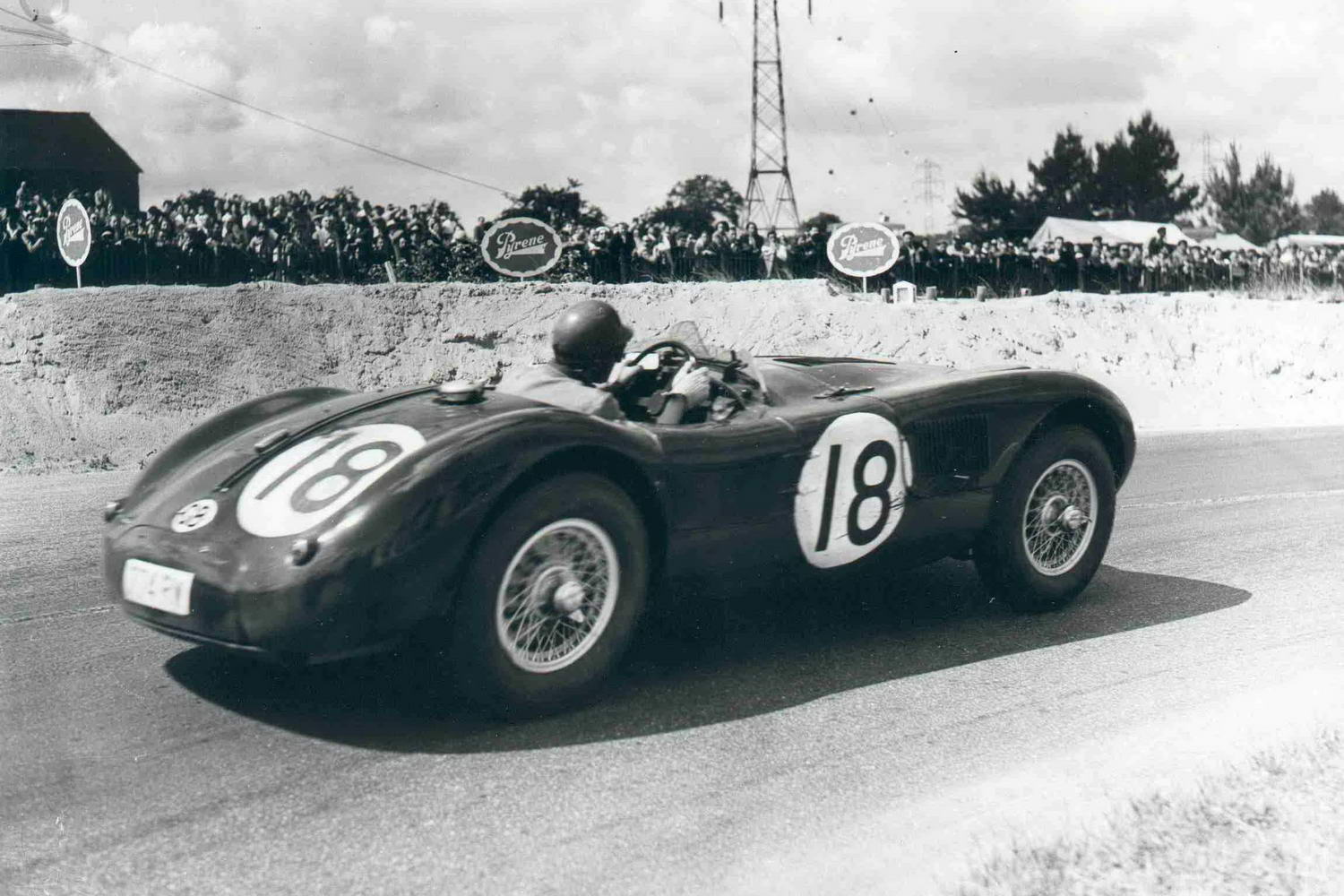

Hamilton’s day of days came in 1953, at Le Mans. He was part of the works Jaguar squad, driving the revolutionary C-Type. A racing version of Jaguar’s immortal XK120 sports car, it was one of the first racing cars to use disc brakes, which gave it a massive advantage over rival cars from Maserati and Ferrari. Hamilton almost didn’t get the chance to deploy that advantage, though, and here we slip into the realms of legend and even fantasy...

That both Hamilton and his co-driver Tony Rolt (himself already well-known for having attempted repeated escapes from the infamous Colditz Castle during WWII) were disqualified before the start of the race is taken as fact. The two had contravened an obscure rule by running some practice laps in a car other than the one they’d use in the race. The Le Mans authorities, always keen to start a fight with British teams, lowered the bureaucratic boom.

According to Hamilton, what happened next was purest farce. “Accordingly, we decided to drown our sorrows in the usual way. After a night of steady imbibing we drifted eventually into Gruber’s restaurant for a cup of coffee. We were sitting there feeling ill, miserable and dejected, when a Mark VII Jaguar drew up outside and William Lyons got out. He hurried over to us with the news that he had paid a 25,000-franc fine and we were back in the race. I looked at my watch; it was 10am; in six hours’ time the starter’s flag would fall. Neither of us had had any sleep, and twenty-four hours of racing lay ahead. We ordered more black coffee and enquired if there was a Turkish bath in the town.”

Hamilton went on to claim that a combination of hair of the dog (brandy) and regular ingestion of champagne during the race, kept both him and Rolt from falling into stupor during the gruelling event. Staggeringly, they won. “We eventually ran out winners by 29.1 miles from Stirling Moss and Peter Walker at an average speed of 105.85mph; the first time the magic figure of 100mph had been exceeded” wrote Hamilton. “By two o’clock we had covered 278 laps, one more than the winners of the previous year, and by three thirty the scoreboard had run out of numbers. When the flag was dropped to signal the end of twenty-four hours’ racing it coincided with my arrival on the line. It was the end of a perfect day’s racing and I had achieved my dearest sporting ambition.”

The thing is, it’s all - apparently - lies. Well, the fact of winning isn’t; Hamilton and Rolt were very definitely the winners, the second in Jaguar’s long and glorious history at the Le Mans, which would culminate in five race victories in the 1950s and two more in the 1980s. The drinking thing, though? Utter rubbish, according to both Rolt, and Jaguar team manager, Frank ‘Lofty’ England. England said: "Of course I would never have let them race under the influence. I had enough trouble when they were sober!” Quite why Hamilton felt the need to embellish his own legend isn’t known. He also, curiously, fails to mention the fact that he was struck in the face by an errant bird during the race, which must have been both unpleasant and uncomfortable.

He and Rolt almost won Le Mans again the following year, falling only fractionally short of beating a much more powerful V12-engined Ferrari driven by Froilán González and Maurice Trintingnant. He would go on to win other prestigious races, including the 12 Hours of Reims, but a second Le Mans win would elude him. He remains the only Irish-born driver to win the French classic - boozed-up or otherwise.

Having suffered terrible injuries in the Portuguese Grand Prix in 1953 (which necessitated surgery without anaesthetic, according to Hamilton: “Fortified with port I could just about stand the pain, but not the thought of the ash on the surgeon’s cigar - which was fully two inches long - falling into my open chest”) and crashing heavily at Le Mans again in 1958, Hamilton finally retired in 1959, bereft at the loss of his great friend, Mike Hawthorn, in a road-car accident.

Hamilton’s name lacks the easy recognition of contemporaries such as Fangio, Hawthorn or Moss, and his Cork roots are unknown to all but a few. He deserves more remembrance than he generally receives, so perhaps the centenary of his birth might elicit a few appropriately raised glasses.

Adrian Hamilton, his son, said: “My dad was one of the last of that extraordinary band of post-war drivers who, hardened by the hostilities, feared nothing and were determined to enjoy every minute of their lives to the maximum. Their enthusiasm for racing was only matched by that for partying afterwards, and we’ll never see their like again. I am fiercely proud of all he achieved and am sure I won’t be alone in raising a glass to him on April 30, the centenary of his birth.”

Hamilton’s autobiography, Touch Wood, is published by John Blake and is available as a paperback or e-book. Duncan Hamilton ROFGO is still in business as a dealer of classic and high-end performance cars.