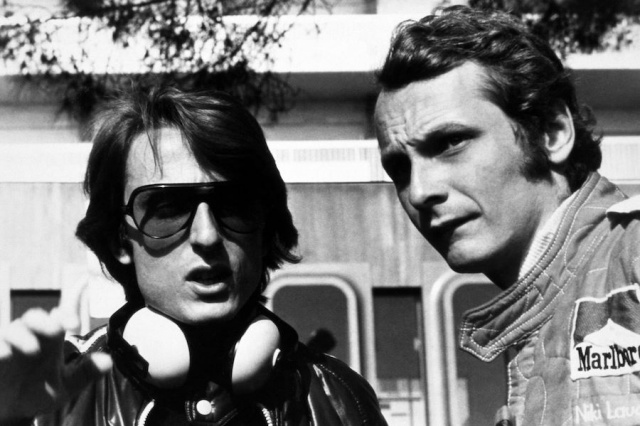

Luca di Montezemolo is a man who knows his onions, assuming that by onions you mean the delicate, precarious business of selling super-fast supercars to the super-rich. For decades, di Montezemolo's name was spell-checkingly-synonymous with that of Ferrari. Back in the early seventies, Enzo himself gave young Luca, barely out of business college, the keys to the kingdom, granting him the manager's gig at a perennially troubled, perennially losing Ferrari Formula One team. Within a season, di Montezemolo had turned things around, brought in Niki Lauda and started racking up wins and titles again.

After a brief absence from the Scuderia, while he carried out some minor tasks such as organising Italy's World Cup 1990 hosting (a job that should forever enshrine him in Irish hearts) Luca returned to Ferrari in 1993, and again turned the team from loser to bruiser, eventually presiding over five back-to-back titles with Michael Schumacher in the driving seat.

But we're not worried about his racing credentials here.

You see, in the nineties Luca also turned the Ferrari road car business around. By the time of his return to Maranello Ferrari's road car range was trading on past glories and the hateful 348 coupe was getting a critical kicking compared to Honda's peerless NSX. Luca's solution? Make Ferraris more like Hondas. It sounds daft now, but it worked - bit by bit, starting with the gorgeous 355, Ferraris became more useable, more practical and more reliable to the point where now, you could take any car from its range (save perhaps the LaFerrari) and, assuming you have a cheque book of sufficient depth, use it as your daily driver.

Ousted from Ferrari just last year, Luca has been saying some interesting things of late, not least about the health/sickness of modern F1, but also about road cars. In a fascinating interview in Motor Sport magazine di Montezemolo said, and I'm paraphrasing here, "the functioning of a car doesn't matter any more. All people care about now are how it looks and how much it costs." For a man indelibly associated with a car maker equally indelibly associated with great engines and towering performance, that's quite some statement to make.

He has a point though. Luca usually does.

Here's a test for you. Go out this weekend and do a bit of test driving. Pick three random models from a given class. Let's say you choose the family hatchback market and you go for a spin in a Volkswagen Golf, a Ford Focus and a Peugeot 308. Now, tell me truthfully - did you notice much of a difference in the way they drove? They all look distinctively different, inside and out, but they're all running 1.6-litre four-cylinder turbodiesels (for the most part) and all drive more or less the same. Years and years of experience of road testing every different car on the planet might give us here at CompleteCar.ie a fighting chance of telling the difference, but for most people they're the same. Cars are converging, and that's something that's going to become more prevalent.

Engineering, in the oily and metallic sense, is also partially an art. Two teams working on similar engines in two different factories, using basically the same amount of steel, aluminium, plastic and copper, will often come up with two totally different engines in terms of response and feel. Drive any Italian car straight after driving a mechanically similar German car and you'll see what I mean.

Electric motors aren't like that. With only one moving part, they don't feel different from one to the other, so that sensation of difference will be smothered. And don't get me started on robotic or autonomous cars. Although all car makers are currently working on differing and different systems, eventually a common, global standard is going to have to be found for all to work around. Eventually, all cars will feel the same.

So, Luca's right. What will differentiate cars in the future will not be the engine, or how they function, but how good they look and how much you pay for them.

In some ways, this is good news. After all, it's quite democratic, because assuming greater convergence between power sources and drivetrains means that the guy buying a €10k city car is, essentially, getting something with the same engineering standards as the guy spending €1,000,000 on a hypercar. The difference will be in the amount of carbon fibre and Swarovski crystals used.

It may also give designers more freedom. If car makers realise (and they pretty much already have) that people care about the car's skin and not so much about what's under it, then perhaps designers will be allowed to bring more flights of fancy to the styling. If the budget for the electric motor and batteries comes down (and it will) then why not spend more on making the car look gorgeous? You'll have to, after all, because it will be the only point of difference between your car and the next.

It bodes well for the sophistication of the car's insides too. After all, Apple CarPlay is just as standard now on the humble Opel Astra as it is on the humbling Ferrari GT4C Lusso - and in either case it is so much more advanced than what we got in the cars I learned to drive in that, frankly, it makes my head hurt just to think about it. In-car tech is predicted to expand rapidly into a multi-gazillion-dollar annual business, so expect your car's cabin, whether family run-around or hypersonic atomic wedge, to become a lot more sophisticated in the next few years.

But will we have lost something? Undoubtedly so, yes - after all, that craft (and craft it most certainly is) of getting 20,000 oily, metallic components to mesh and move in perfect, reliable harmony, is still a thing of wonder to so many of us. Cars mean something, something far more than the sum of their assembly. It's why there's no magazine called What Fridge? Or website called CompleteCoffeeGrinder.ie. Turn the mechanics and engineers out on the street and call in the software brigade and we will have, without question, lost something.

I think there's hope though. Tesla is a bit of a shining beacon of future cars that are still fun to drive and technologically fascinating. And any car that includes a Spaceballs gag in the performance settings can't be dreary, right? And there are others - Morgan's gorgeous little electric three-wheeler EV3 for instance. How can you fail to be charmed by a car that appears to be wearing a monocle, and which can provide hours of guilt-free, polar-bear-friendly fun?

Luca has a point. He always does. He's clever. But I don't think even he thinks that we're going to give up our 125-year passion for cars just because we're changing the ways in which we think about them.